Question:

I’m in a writing circle with a few other tenure-track friends, and one of them keeps giving me detailed edits that don’t feel like improvements to me. She’s well published in her field, which is close to mine, and she won a big grant recently. How do I know if she’s the better writer? How do I determine if and when I should emulate her writing style?

– Anonymous, Film Studies

Dr. Editor’s response:

I can’t tell you how to figure out if your colleague is a better writer than you are. There’s some limited evidence that suggests that well-written papers are more likely to get published than papers that aren’t well-written (e.g., Fages 2022; Feld, Lines & Ross 2022). So it may be that your colleague’s success with publishers and grant funders are indicators of the quality of their writing – or it may be that we’re seeing the Matthew effect of accumulated advantage at work in your colleague’s CV (Bol, de Vaan & van de Rijt, 2018). Or maybe I’m attempting to construct a pattern out of too small a dataset!

Rather than wondering whether to accept or reject your colleague’s suggested edits, dear letter-writer, I’d encourage you to identify your own favourite academic writers. These could be researchers who are highly cited and highly funded, or they may be authors you first encountered in graduate school or through social media threads like this one from March 2022, initiated by Jill Walker Rettberg:

Which academics write BEAUTIFULLY? I want to read writers who weave language, who dare to be personal, who write speculative essays or personal criticism and are theoretically or philosophically or analytically exciting, innovative or generative. Who should I read?

— Jill Walker Rettberg (@jilltxt) March 26, 2022

Ideally, I’d like you to find authors who write in the same discipline as you, since the best writing is tailored to its audience and context. Once you have a few examples of writing that you admire, and that you’d like to emulate, I suggest saving it as a Google Doc, and removing any tables, footnotes, references, or acknowledgements.

Then, I’d like you to copy that Google Doc text, and paste it into the “references” box over at writingwellishard.com:

With the support of a small team, I’ve been building Writing Well is Hard since the start of 2022. This free tool helps you to identify the writing characteristics of the best academic writers – however you choose to define “best” – and to compare your own writing to your chosen reference.

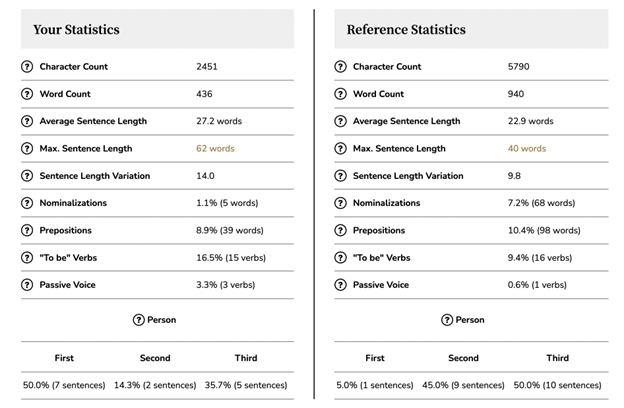

Click the “analyze” button and you’ll see a list of stats that enable you to compare your own writing to your chosen sample:

Using the tool should be fairly intuitive. Hover over the little question mark to read more about each feature of writing analyzed in the tool. You’ll also receive detailed graphs, showing you how many of your sentences have particular word counts, as well as where you have clusters of nominalizations, prepositions, “to be” verbs, and the passive voice. With each graph, you’ll find more detailed explanations of each writing feature, as well as links to blog posts and old “Ask Dr. Editor” pieces that I’ve written, which have more nuance than we could include on the site without compromising its readability. Knowing where you have clusters of these writing features enables you to focus your editing on specific sections of your document, so that you can target your revising on where it is needed most.

If you want even more detail than we could fit on a single webpage, then enter your email address in the banner at the bottom of the site to receive a free 13-page PDF with explanations, editing tips, and links to additional resources.

What I like about Writing Well is Hard is that – unlike other, comparable sites such as “The Writer’s Diet” and “Hemingway Editor” – you’re able to calibrate the tool. You can compare your draft article manuscript to published peer-reviewed articles in your target journal, or your own draft grant application to one from a friend, or from Open Grants. No more apples to op-eds: you decide what counts as good writing, and our tool visualizes where and how your own work compares.

Of course, Writing Well is Hard is just a robot. It can only detect what it is programmed to detect; it can’t tell you if a sentence is unclear, if an example is misleading, or if your writing sounds like a piece of legalese.

The belief that dull, simplistic writing is superior to ornate prose because “we write science not poetry.” Delivering striking insights about human behavior in the style of tax code does not make you a better scientist.

— Timothy J. Valshtein (@tjvalshtein) April 22, 2022

It may be that your colleague from your writing circle is providing you with that human level of feedback, or it may be that you need to hire an editor for your next major manuscript.

I can’t tell you if your colleague is a good writer or not. No editor can. We’re not qualified to place all writing on a linear scale from “best” to “worst.” Most of the editors I know would reject the idea of a single scale for all writing, or the idea that there is a single way to write well. Instead, we can make suggestions for how you might alter your text to increase its readability, persuasiveness, and efficiency. But it’s up to you as the subject matter expert – the person who best knows your readers, your field, your contexts – to determine which edits you accept and which ones you reject.

Writing Well is Hard can help you to see your own words in new ways. My goal is to empower you to feel competent at making your own decisions about what is best for your work. It sounds, dear letter-writer, like you’re not yet comfortable doing so. I hope that this new resource will help you to better understand what writing well looks like to you.